Sources: Facebook (June 21, 2016) || Instragram (June 21, 2016)

Consequences of the Frame

By Melissa Lo

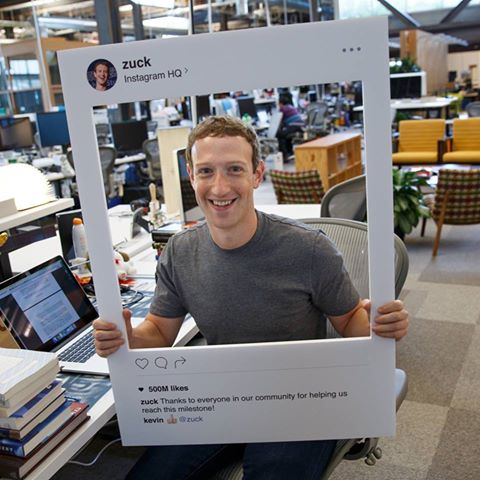

On June 21st, 2016, Mark Zuckerberg took to Facebook to congratulate Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger on Instagram hitting 500 million users per month. The milestone warranted a tailor-made prop: an Instagram interface-come-to-life. Zuck held the frame up to his face, perpetrating a cute set of fictions: that Zuck would post such a “photograph” of himself to his Instagram feed; that it would garner a like from each of Instagram’s 500 million users; and that it would win [thumbs-up emoji]-approval from “kevin” — i.e. Systrom — himself. But the presumptions of those fictions traded on the reality of everything beyond the frame. What Zuckerberg posted to Facebook was a photograph of everything but the “photograph” itself.

“[W]hy choose (why photograph) this object, this moment, rather than some other?” Roland Barthes asks in Camera Lucida.[1] Upon further consideration, Barthes decides that “[w]hatever it grants to vision and whatever its manner, a photograph is always invisible: it is not it that we see.” Barthes’s paradox toys with how we read snapshots and candid portraits of all kinds. On the one hand, inspecting an image of the people, places, and things that crowd into a photographic frame requires that we momentarily forget the physical material supporting that image. On the other hand, the French theorist refers to the people, places, and things that photographers choose to leave out. The framing or reframing of a subject — whether at the moment a photograph is taken or in the laboratory (or in Adobe PhotoShop) — argues for longevity and endurance. But that which endures can only be understood by remembering that which did not survive the photographer’s cut, and all that may very well remain “invisible.”

The Zuckerberg photograph is a masterclass in funny combinations of pre-meditation and accident. Careful coordination brought all these elements together: the posterboard prop was someone’s idea. The prop’s paratext had to have an author. Another employee was likely tasked with making it into a three-dimensional reality. And there had to be a scheduler or assistant responsible for reminding Zuckerberg of his photo shoot. By contrast, the posted photograph works at cross purposes with the prop frame itself. Such 3D Instagram interfaces are typically deployed against well-orchestrated backdrops — a world-premiere red carpet, or the photo booth at a wedding. No such occasion here. Instead, we’ve come across this tech behemoth during an office-wide lunch break. Soon enough, engineers will come back to their desks to adjust Facebook’s algorithm so that every user’s news feed emphasizes her friends and family.[2] They’ll churn out new combinations of 0s and 1s for app install advertising.[3] And it will be Christmas in June as the Facebook Business team begins strategizing on a tactical guide that will help marketers plan their 2016 holiday campaigns.[4] Just a casual day in the office of one of the the top five most valuable companies in the world.[5]

Zuckerberg has had an outsized hand in creating our era of disruption; he even coined its favorite rallying cry, “move fast and break stuff.” (As of 2014, Zuck announced that Facebook is now poised to “move fast with stable infrastructure,” but it just doesn’t have the same ring to it.)[6] It’s hard not to compare Zuck with the Gilded Age’s captains of industry, who distributed steel and liquidity as they announced that “God gave me my money” (John D. Rockefeller) and “I owe the public nothing” (J. P. Morgan).[7] In summing up their own circumstances, or expiating themselves through philanthropy, these men also strove to master their own images. Morgan hated being photographed for fear that his rosacea was all anyone would see.[8] Rockefeller kept a low profile in visual culture, barring photojournalists from his home, and refusing to supply magazines with photographs of his family or workplace portraits.[9] But when industrialists did pose for the camera, their photographers made efforts to capture them at their desks. This portrait of Andrew Carnegie is a case in point. Here, the rags-to-riches magnate takes a break from his stuffed cubbyholes and furious correspondence. The pen in his right hand signals that he won’t pose for the camera for too long. But, still, he lets us linger over his rolltop desk whose upper-most surface is populated by family photographs and personal certificates, an inkwell and its flamboyant feather, plus two little flags that do loyal, patriotic work. When Carnegie’s walls aren’t outfitted with accounts-filled drawers, they are covered in photographs. And though it would be hard to identify any of the men that surround the man himself, these photographs conjure a genealogy, and multiple sets of relations, that fixed how Carnegie would make steel for America.

A desk made expressly for 21st-century speed and destruction requires different objects of plenty (and many fewer photographic prints). This is what the Zuckerberg 2016 portrait captures so well. Zuck sits in an expansive, airy open-plan office. The stack of books to his right tells us that Zuck’s a reader. The Lumio booklight says he reads for innovation. A little stuffed animal speaks to the child-like whimsy that accompanies a Fantasia sorcerer costume for Halloween.[10] And because Zuck has just turned away from his laptop, we also learn that he’s a Mac guy. In the hours after this photograph was posted, commentators rushed to dissect meaning out of this computer, breathlessly reporting on the security precautions the internet mogul had applied to the laptop’s camera and mic jack.[11] But therein lay a neat irony: while Facebook’s motto in June 2016 was about “making the world more open and connected,” all that tape belied the requisite security precautions in a digital culture that surveils and intrudes as much as it connects.[12]

Nevertheless, in a Valley that runneth over with kings and king-makers, growth must be celebrated. The photograph is an expression of gratitude for the enormous user numbers that Instagram has posted (i.e. approximately the populations of the United States and Pakistan combined). In his caption, Zuck writes that the post is also a “tribute” to all of the platform’s users — all those content-generators who, while rarely getting paid, work toward the livelihood of the platform, throwing open windows onto worlds untold and keeping the lights on in Menlo Park, California.[13] But it is also a message from one founder to another — or, really, from acquirer to acquired: thanks for doing right by our shareholders, thanks for keeping the momentum alive. But the picture relegates that partnership to its literal subtext. It takes employees largely out of the picture. It puts users aside. Because, ostensibly, the subject of the “photograph” is the man who created Facebook, the empire he’s built, and the necessary accessory that Instagram is to that project.

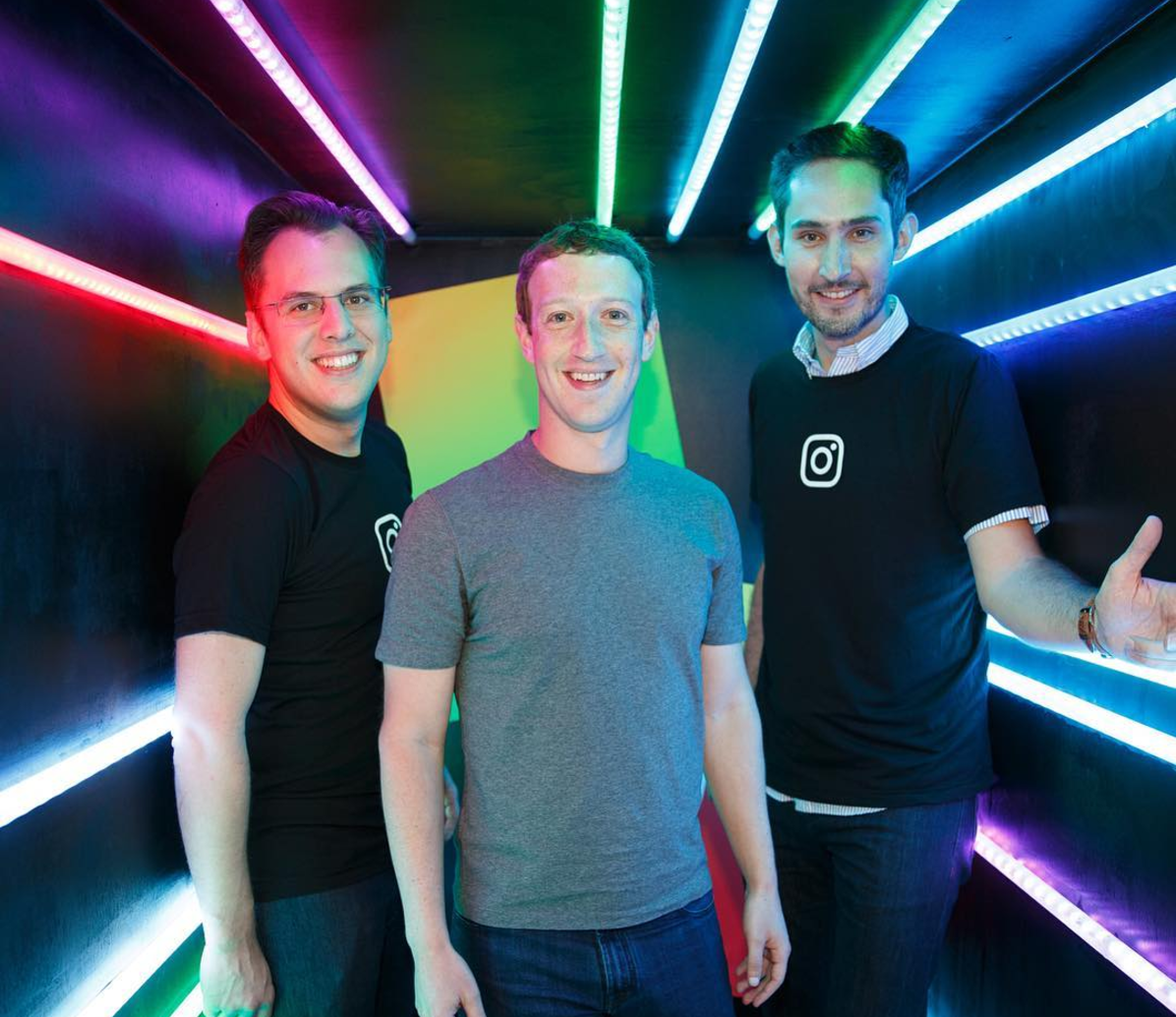

On June 21st, 2016, Mark Zuckerberg posted the very same caption to another social media feed: Instagram. But his thanksgiving was accompanied by a different picture — this time, a portrait of a triumvirate. Zuck is flanked by Systrom and Krieger in a tight black box illuminated by neon lights and decorated with what looks like a very large slanted post-it note. Whether for the sake of variety or correction (funnily enough, Zuck appears to be wearing the same t-shirt in both June 21st pictures), this image recalls a snapshot of Steve Jobs, John Sculley, and Steve Wozniak when they brought the Apple IIc to market. There is a striking difference between the two images. At the 1984 Apple Forever Conference, Jobs, Sculley, and Wozniak were offering an object to hold in your hands. Zuckerberg, Systrom and Krieger offer only themselves and Instagram’s logo. Internet moguls might harvest code, but these particular moguls traffic in images and their circulation, visual reproduction and its attendant commentary. This photograph tells us that such ventures amount to a black box made by these leaders and tailored to their own dimensions.

Black boxes are, as Bruno Latour has described them, the mechanisms by which “technical work is made invisible by its own success. When a machine runs efficiently, when a matter of fact is settled, one need focus only on its inputs and outputs and not on its internal complexity.”[14] This logic applies startlingly well to the photograph of Zuck, Systrom, and Krieger. For this image reminds us that our own era’s most visible black boxes, like Facebook, are expected to contain little more than visionaries — and, in this case, three white men who, with extraordinary fortitude, have forever changed our visual and computational landscapes. This is not to take away from the enormous quarterly burdens these three individuals bear, or to cast aspersions at their once-improbable and now very real achievements. But it is to say that their iconicity is the result of a neoliberal society where corporations must be measured by their top dogs (cf. Apple and Steve Jobs; Uber’s erstwhile CEO Travis Kalanick). CEOs are held up as input, output, and mechanism; they become the apotheosis of the intricate corporations they lead. Small wonder the images they produce of themselves, and especially the pictures they post to the platforms they create, hold our attention.

What, in the end, makes a picture significant? As of February 2017, Facebook’s Applied Machine Learning group has begun to answer this question with a complex classification scheme. Their sophisticated AI systems can now identify the major features of any picture without clues from any accompanying text or tagging. Apart from identifying locations, monuments, and even the genre of any given picture, they are now able to describe the action that a photograph freezes in time: “people walking,” “people riding horses,” and “people dancing.”[15] What, then, would these algorithms make of the photographs I’ve made such a fuss over? “Men standing.” “Man holding a picture.” But I wonder if they would be able to identify that frame. I wonder about invisibility. I wonder what will happen to everything that was cropped out of the frame.

----------

References