Source: Techcrunch - Arrington and Zuckerberg, TC Disrupt (September 11, 2012)

Fireside Chats, Tech Spectacle, and

the Making of Mark Zuckerberg

By Li Cornfeld

San Francisco, September 2012:

A young Mark Zuckerberg sits in a brown leather armchair, animatedly holding a microphone. In a matching armchair set beside him, Michael Arrington, founding editor of TechCrunch, looks quizzical. Onstage behind them, a digital backdrop labels the interview a “Fireside Chat.”[1]

Source: Facebook - Mark Zuckerberg and the Gant Family (April 30, 2017)

Facebook, January 2017:

Zuckerberg announces, via Facebook post, a New Year’s resolution: before the end of the year, he will have visited all fifty states in America, part of an effort to glean insight into the impacts of technology and globalization on people across the country.[2] The ensuing photographs, which include images of Zuckerberg dining with farmers in Wisconsin and crouching beside Civil War gravestones in Mississippi, look an awful lot political campaign photos, fueling speculation that Zuckerberg plans to run for President of the United States.[3]

Source: Facebook - Zuckerberg at Vicksburg National Military Park (February 22, 2017)

A fireside chat at a tech conference, like a CEO travel itinerary that resembles a political campaign tour, aligns with broader trends in the tech industry, where corporate promotional practices are regularly styled as forms of civic leadership. Zuckerberg’s 2012 appearance at TechCrunch Disrupt San Francisco, the signature conference of AOL’s TechCrunch blog, provides a pretext for the modes of presidential presentation that characterize his more recent public image. At tech industry events such as Disrupt, organizers draw on the legacy of presidential oratory by staging public conversations with industry leaders as sites of revelatory exchange: fireside chats, simultaneously intimate and officious.

Before returning to the debate over whether Zuckerberg’s tour of America portends a national political campaign, this essay looks at the Fireside Chat of 2012 in order to glean insight into how the tech industry’s modes of exhibition borrow from political tradition. The first Fireside Chats, of course, took place during the Great Depression and the Second World War, when President Franklin Roosevelt used radio broadcast to calm an anxious nation by laying out his administration’s plans for addressing the issues at hand. As adopted by the American tech industry, events known as fireside chats take place in a variety of settings; TechCrunch is far from the only outlet to employ the term. Some chats, like Zuckerberg’s, take place at industry venues that attract attendance from companies throughout the industry and around the world. So too do individual corporations include fireside chats as part of regularly scheduled internal programming for company employees. (For a sendup of the practice, see a 2014 episode of the HBO sitcom Veep, in which the Vice President of the United States seizes on her public chat in front of a fictionalized tech company as an effective medium of political messaging.)[4]

These twenty-first century iterations of fireside chats mark significant departures from many of the conventions established by FDR’s radio addresses. They take place in person rather than via broadcast and feature interviews rather than direct address, to name just two of the most obvious alterations of the form. Such basic distinctions merit asking: why borrow from the lexicon of political media and twentieth century governance? What cultural characteristics associated with the Roosevelt radio tradition does the stage spectacle render visible?

The Meaning of the Fireside Chat

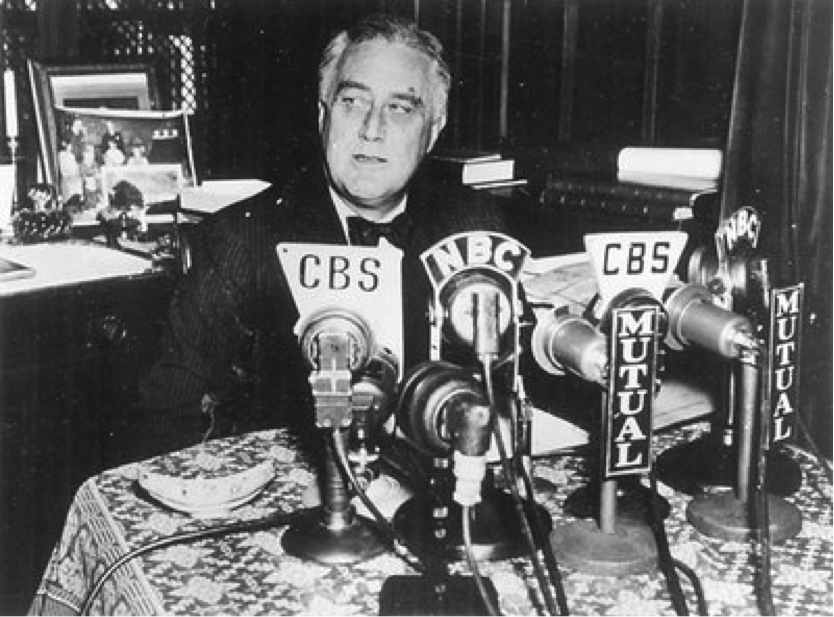

From its inception, the very locution “fireside chat” functioned as a public relations strategy: the coinage originated in a press release issued by the Columbia Broadcasting System in advance of Roosevelt’s second presidential radio address.[5] Taken up by the press and eventually by the White House itself, the term conjured a cozy familiarity, framing presidential oration as avuncular conversation. Publicity photos of the chats show the President at a desk in front of microphones, with books, curtains, and picture frames in the background behind him, as if to suggest that the broadcasts linked the President in his parlor to American parlors across the country. If a Fireside Chat took place on a hot summer evening when the nation’s hearths were dark, the social sensibilities associated with the fireside persisted. Similarly, when TechCrunch styles the headline event of its signature conference as a Fireside Chat, rather than something like a more traditional keynote address, it likewise signals an apparent informality of a highly conventionalized presentation.

Franklin Roosevelt, Fireside Chat, Undated

The Fireside Chat at TechCrunch Disrupt in the fall of 2012 marked Zuckerberg’s first public interview since Facebook’s billion-dollar IPO the previous spring. The booking not only reflected Zuckerberg’s power as a headliner, it also heralded the growing prominence of the conference, a “breathless gathering in Silicon Valley’s Liturgical Calendar,” as the rival blog ValleyWag would later quip.[6] An event that functions in part as a showcase of splashy tech startups, Disrupt attracts throngs of venture capitalists looking to fund new enterprises, executives looking to acquire them, and entrepreneurs angling to position their products at the forefront of the industry’s latest trends. In 2012, Zuckerberg served as both an aspirational model to founders of young startups and also as an industry leader whose business plans could signal emerging areas of technological development ripe for investment. Meanwhile, for the global press covering the event, Zuckerberg embodied an industry gaining increasing visibility in public life.

Surveying the standing-room-only crowd lining the auditorium at the start of the session, Zuckerberg remarked on the size of the crowd. Facebook had held company conferences in the same space, but, he said, the TechCrunch event was bigger. Arrington, seated beside him onstage as the “moderator” of the chat, conceded that conference sessions earlier in the day had sparser attendance. “I think,” he told Zuckerberg, “they want to hear what you have to say.” The ensuing thirty-minute interview touched on a range of topics, from the performance of Facebook stock to the future of mobile interfaces to emerging intersections of technology and culture. Viewing footage of the chat just five years later, it can be jarring to watch how the chat holds up now-ubiquitous technologies as a novel (“I do everything on my phone!”) and captures the attention of a room of tech industry insiders.[7]

The chat offered Zuckerberg a unique opportunity to outline his vision for the future of Facebook, and for the industry more broadly, in front of a large gathering of people who could help make that vision a reality. While the Zuckerberg/ Arrington exchange hardly belongs in the pantheon of great American oratory, it builds on a tradition set by the original Fireside Chats, through which the President marshaled American citizens as advocates of his national policy agenda.[8] At conferences like TechCrunch Disrupt, fireside chats serve a similar function, where the tech industry stands in for the nation, and where public opinion revolves around corporate jockeying rather than governmental agenda. Where the CBS press release publicized the radio as the medium that brought the President to the people, with the Zuckerberg Fireside Chat, TechCrunch made the medium of transmission the conference spectacle itself.

The Image of the Fireside Chat

An irony of the tech industry’s resuscitation of the fireside chat is that as the practice entered the industry’s lexicon, it lost its early cache as a product of media technology. Celebrated in the 1930’s as a cutting-edge use of a new medium, the original Fireside Chats enjoyed close association with technological innovation by virtue of their transmission as national radio broadcasts.[9] TechCrunch likewise made the Zuckerberg chat available to anyone with an internet connection by a relatively recent technology of our own era, streaming web video. However, conference-goers nonetheless clamored into the room in order to see the chat in person. Contra Arrington, it seems that what Zuckerberg had to say mattered to audience members at least much as did the opportunity to see him say it live and in the flesh.

To cultivate a sense of intimacy over the radio, Roosevelt at times drew attention to the radio as a medium of live transmission. For example, on one much remarked upon occasion, he interrupted his own address to ask for a glass of water.[10] After taking a sip, but before continuing with his remarks, the President explained to his listeners: “my friends, it’s very hot here in Washington tonight.”[11] To a nation unaccustomed to close encounters with national leaders, hearing the president pause to drink his water constituted an uncanny form of access to the living body of the President. Indeed, the effect proved so charming that scholars have since wondered whether Roosevelt in fact required a drink or merely professed the desire in order underscore the liveness of the broadcast and forge a connection with his listeners.[12] As John Durham Peters writes in his history of communication, “by letting his audience in on his thirst and thus revealing the finitude he shared with them, FDR proved his sincerity. He was ‘one of us.’”[13]

Looking at the Zuckerberg Fireside Chat – rather than listening to it – shows how the event utilized its visual sensibility to evoke the intimacy that Roosevelt found in radio. A live interview that conference-goers attended in person would not seem to require such demonstrations of human vitality in order to signal the humanity of the speakers. Yet in some respects, Zuckerberg’s signature gray t-shirt and sneakers serve a similar function, marking Mark as just “one of the tech bros” if not exactly “one of us.” Arrington, for his part, compounded the normcore aesthetic by dressing for the headline event in short-sleeves and loafers. While a dressed-down sartorial sensibility makes the tech industry no less regimented than fields with more formal aesthetics, it indicates the perceptions of informality on which the Fireside Chat capitalized. Rather than signal a relaxation of tech dress codes, the stage picture created by the Fireside Chat affirmed the field’s sartorial mores and underscored that, however successful Facebook or TechCrunch became, their founders continued to identify as part of the startup community in formation at the conference.

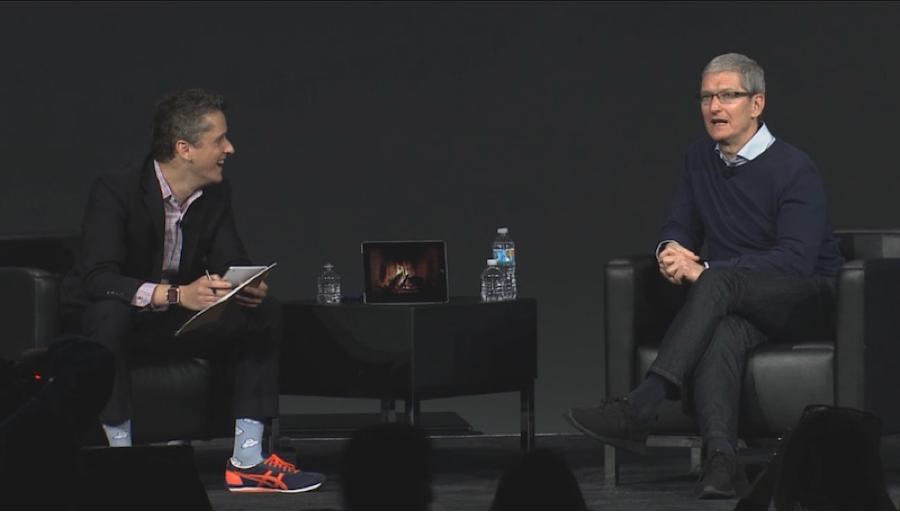

At the same time, the presentational stylistics of the Fireside Chat hailed Zuckerberg as extraordinary. He was, after all, the headline event, seated onstage in front of the audience, not a man among the crowd. And while audience members variously stood along the edges of the room or wedged together in rows of folding chairs, Zuckerberg and Arrington sat onstage in large, brown leather armchairs. Similar armchairs are a staple of fireside chats throughout the tech industry, perhaps in part because they call to mind chairs that might well be set beside a hearth. Although exceptions exist, this predilection for stately armchairs, rather than the modernist aesthetic that dominates tech industry corporate campuses, more effectively evokes the titular fireside. (In a few goofy examples, conference organizers make this explicit; when Apple CEO Tim Cook addressed the BoxWorks conference in 2015, a small digital video of a blazing fire played on a laptop propped up beside him.) The stage picture of the contemporary fireside chat thus nods to the rhetorical frame and theatrical sensibility of its progenitor while positioning speakers in the presidential role.

Source: MacRumors - Aaron Levie and Tim Cook at BoxWorks 2015 (September 29, 2015)

At Disrupt, the stagecraft of the Zuckerberg Fireside Chat drew on the affordances of the live event in order to cultivate a sense of stately intimacy. At the same time, it anticipated a still broader audience, comprised of viewers who streamed the event remotely, readers of news outlets that ran photos of the chat, and those of us looking at the documentation as an object of historical record years down the line. For our benefit – and for TechCrunch’s – Zuckerberg and Arrington addressed the audience while seated in front of a bright green backdrop, splashed with text reading “TechCrunch” and “TechCrunch Disrupt SF 2012.” On the sides of the stage, the brandscaping continues: the slide that labels the session “Fireside Chat” depicts the Golden Gate Bridge rendered in TechCrunch’s signature green. It lists Zuckerberg’s affiliation as “Facebook” and Arrington’s affiliation as “TechCrunch.” Arrington is billed first.

That the 2012 Fireside Chat named TechCrunch as Arrington’s affiliation functioned as a public relations statement of its own. The year before, Arrington had been ousted as editor of TechCrunch over journalistic ethics violations, following an announcement that he had founded a venture capital firm, dubbed CrunchFund. Coming from a man whom Time had once listed among the world’s most influential people because of his blog’s coverage of the tech industry, the announcement smacked of self-dealing: CrunchFund would invest in precisely the sorts of startups covered by the blog.[14] In response to outcry over the scandal, TechCrunch announced that Arrington would no longer work at the blog, but would remain central to the company.[15] By serving as moderator of the high-profile conference session, under the TechCrunch moniker, Arrington demonstrated his persistence as its public face. If Zuckerberg stood to benefit from an opportunity to address TechCrunch Disrupt conference-goers, the man seated onstage beside him stood to benefit from the visibility afforded by his role as Zuckerberg’s interlocutor. The Fireside Chat thus showed how, absent a more traditional editorial platform, Arrington would continue to position himself as an influential arbiter of success.

More broadly, the brandscaped backdrop stages a visual reminder of how the tech industry’s cultural institutions provide a frame for Zuckerberg’s self-presentation. The TechCrunch-themed stage design asks anyone looking at the image to take stock of TechCrunch’s role in making Zuckerberg available to the public. His public persona rests on a complex network, comprised not only of Facebook’s public relations teams but also of companies who stand to benefit from their association with the young mogul whose very celebrity they help shape. By putting industry leaders into conversation under the auspices of a presenting organization, the Fireside Chat functions as one place where the industrial complex that goes into the production of Zuckerberg’s public persona is on display.[16]

After the Fireside Chat

Five years after Zuckerberg’s post-IPO fireside chat, he is far from the only corporate CEO said to be contemplating a presidential run. “With Trump in the White House,” reported a recent New York Times headline, “Some Executives Ask, Why Not Me?”[17] Yet even if experience in public service is eroding as a requisite of the American presidency, the Times noted that few executives are equipped to launch a campaign with the name recognition that Trump had cultivated through branding and reality television. In that context, Zuckerberg is remarkable as an increasingly recognizable public figure. (His uniform ensemble functions in this sense as a branding mechanism, even as it signals his startup affinity.)

The tech industry’s presentational exercises are quite different than the reality television shows that propelled a business magnate into the Oval Office.[18] Rather, the tech industry has its own modes of spectacular exhibition – some of which, as with fireside chats, invoke more traditional modes of political communication. Indeed, in the wake of Zuckerberg’s recent photo-ops in locales across America, some political commentators have pointed out the similarities between a national political campaign and “a corporate goodwill tour,” in that both practices center on forging relationships between high-profile figures and the general public whose interests they claim to represent.[19] Such observations, which identify Zuckerberg’s recent activities as expansive business tactics rather than as a burgeoning political campaign, perhaps allay concerns over how Facebook’s news algorithms and user analytics would drive Zuckerberg’s political fortunes, were he to instrumentalize Facebook as a tool of voter mobilization or state surveillance.[20]

Yet the very debate over the meaning of Zuckerberg’s road trip photographs suggests that the cultural infrastructures of the tech industry are themselves a political force to be reckoned with. Just as the original Fireside Chats bolstered FDR’s fame as a national figure while humanizing him as relatable public servant, so too did the Zuckerberg Fireside Chat of 2012 spectacularize the image of the young CEO while also presenting him as an accessible leader. And while interest in Zuckerberg in the fall of 2012 ran especially high, fireside chats throughout the tech industry cultivate the public personas of industry players according to presentational modes associated with political leadership.

Cast in the Roosevelt role, Zuckerberg may well keep his focus on industrial stewardship. If speculation over his Presidential bid bespeaks muddied boundaries between government and industry, it also shows how the tech industry’s practices of public presentation shore up political power. Looking beyond Zuckerberg to the confluence of actors and activities that sustain his public image shows an industry that increasingly positions its leaders to step into the spotlight, on conference stages and in public life.

----------

References